If you think it is possible to identify a lie by eye movement and conclude that someone is lying just by observing this indicator, it’s better to read carefully what will be exposed next. You´re a about to understand the eye movement misconceptions

♦ TIP

Another study (among many), published in the journal PLoS ONE contradicts the widespread notion that you can assert that a person is lying by the way their eyes move.

♦ FACT

Eye movement is not a reliable indicator of lying. Let’s see the reasons.

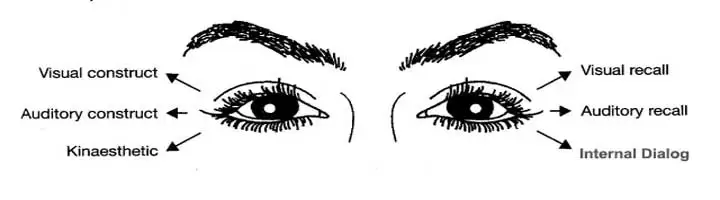

According to non-verbal communication enthusiasts, a person whose eyes move to the left means they are remembering something, while a shift to the right means they are creating a version (in many cases, this means lying). Here began the eye movement misconceptions.

When you listen to someone like that speaking, you are enchanted… Many of them have an excellent oratory and can reproduce the content of books orally.

Possessing a good memory, the speed with which they can elaborate their arguments is surprising. However, the wonder stops there….

Isn’t there people who fall for the foreign boyfriend scam despite all the warnings and numerous news reports on the subject? Human behavior is like that.

You’ve made it this far, you can also see my 8 TIPS to become an expert in:

LIE ANALYSIS

Is the available knowledge for the population reliable? Eye Movement Misconceptions

In the trainings I conduct, I have been promoting a critical vision among students about what they will encounter, courses that will be offered by unqualified people, and literature on body language that is nothing more than a copy of previously published books…. and also about the risks of using pseudoscience as a strategy of authority in persuasive communication.

I like a definition that philosopher Frankfurt (2005) gives for “bullshit” as “something that is designed to impress, but was constructed without direct concern for the truth.

♦ ATTENTION

There are many ways to hide intentions, and there are people especially capable of doing so.

51 renowned researchers signed as authors of a study on the reliability of books and training offered to the public, arguing the following (Denault et al., 2020, p.2):

Unfortunately, dubious concepts about non-verbal communication are widely disseminated, especially on the Internet and in books aimed at the general public, as well as in seminars and conferences (things like: “body language never lies”).

The use of such concepts can have negative and perhaps even disastrous consequences (Denault, 2015; Kozinski, 2015; Lilienfeld & Landfield, 2008). For example, security and justice professionals who are not familiar with the “peer review” process may be led to believe that these dubious concepts are scientific and confer them a completely unjustified authority (Jupe & Denault, 2018). [our emphasis]

How is it possible to spread myths as acceptable “tips” on Eye Movement Misconceptions?

The figure below was taken from a Brazilian NLP site. Notice the inclusion of the word “probable” (provável) in the title of the figure below.

♦ FACT

The inclusion of the word “probable” will help to “explain” discrepancies, in case the technique does not work and any questioning arises.

Equivalent Image in English

Another example of how to camouflage low-quality scientific information. On a behavior portal, the following article exists:

♦ ATTENTION

In this specific case, the caveat is that indicators may vary with the situation and the person [the word “variar” in Portuguese] (what’s left not to vary then?) Beware of this type of article. Stay alert!

What are the reasons people consume pseudoscience? What are the risks of pseudoscience?

The authors raise some of these reasons (Denault et al., 2020, p.8):

The reasons for irrational beliefs have been the subject of extensive scientific literature. People’s critical thinking skills, political and religious ideologies, as well as cognitive skills and scientific knowledge are some of these reasons (…).

But why do some organizations in the areas of security and justice resort to pseudoscience and pseudoscientific techniques?

For an international scientific community that has published thousands of peer-reviewed articles on non-verbal communication, it may seem surprising that these organizations adopt programs, methods, and approaches that, at first glance, seem scientific, but, in reality, are not. We offer five hypotheses about why some organizations turn to pseudoscience.

Then, they present five reasons for the consumption of pseudoscience:

-

- Organizations have real problems to solve… So if someone claims to have developed a method that solves the problem, the temptation to test such an approach is quite large;

- Not all decision-makers have skills to discern what is truly scientific knowledge;

- Many decision-makers ignore the importance of science;

- The risks of pseudoscience are underestimated by the organizations that adopt it;

They raise that part of it is the researchers’ own responsibility. About this, they argue (Denault et al., 2020, p.8):

Finally, when organizations in the areas of security and justice have unrealistic expectations stemming from television series and other popular media, and turn to pseudoscience, part of the responsibility lies with the international scientific community (Colwell, Miller, Miller, & Lyons, 2006; Denault & Jupe, 2017).

Indeed, “the scientific process does not end when results are published in a peer-reviewed journal. Broader communication is also involved, and this includes ensuring not only that information (including uncertainties) is understood, but also that misinformation and errors are corrected when necessary” (Williamson, 2016, p. 171).

Regarding the risks of pseudoscience, I have been arguing for over a decade that TV series are good for entertainment, but help to disseminate miths lik eye movement misconceptions on lying.

♦ TIP

I have long explained that behavior analysis of artists, politicians, and athletes, especially those conducted by people without any scientific training, are forms of entertainment.

These analyses often expose people to ridicule, raising hypotheses about their emotions and other private behaviors. Normally, this exposure of the subject is done by people without any real preparation.

A well-prepared person, with scientific and ethical knowledge, does not conduct public analyses. The Code of Ethics of Psychology, for example, prohibits a psychologist from participating in behavioral analyses of specific people in the media. This seems to me like the freak shows of the 19th century, revamped. At that time, it was common for people with deformities to be exposed for the public to see them. Today, we have YouTube and other networks to perform the same task.

I have also long been dedicated to clarifying the myths and risks of pseudoscience that arise from scientific works. To delve into my arguments and examples, see the most known and widely disseminated myth – that 93% of communication is non-verbal:

Recent research that debunks the myth of lying through eye movement

Let´s see another ponint of view abort the eye movement misconceptions.

Researchers from the University of Edinburgh and the University of Hertfordshire (Wiseman et al, 2012) conducted a series of experiments to put this belief of neurolinguistic programming to the test. At the end of the article, see a list of other studies that reach the same conclusion.

They recruited 32 right-handed subjects, recording their eye movements when they lied or told the truth. After analysis, there seemed to be no connection between eye movement and the truthfulness or falsity of the participants’ statements.

In another experiment, the researchers showed 50 volunteers some videos. Half of them received information about lie detection techniques through eye movement, coming from NLP, while the other half were not informed.

They were then instructed to identify which people were telling the truth or lying. Based on the results, the researchers found no link between eye movement and truth-telling or lying. There was also no significant difference in the accuracy assessment of those informed about NLP and the other subjects.

Reading a book of NLP techniques is like seeing the juxtaposition of parts of theories without any commitment to technical rigor in articulating different theoretical frameworks.

The ordinary citizen, without the capacity to analyze the feasibility of these literary fantasies, believes that what is there is scientific (especially since talking about its supposed scientific basis is a known technique in the diffusion of NLP). They will notice the flaws during the attempt to put their knowledge into practice.

Based on scientific evidence (e.g., Thomason, Arbucklet & Cady, 1980), it is possible to say that eye movement is related to long-term memory processing.

In this case, it would be possible to use this indicator to notice if the person rehearsed a response (if there is no eye movement) because they do not have to “search” for information in their long-term memory, which is very different from saying they are lying!

You’ve made it this far, you can also see my 8 TIPS to become an expert in:

LIE ANALYSIS

The areas of the brain work together, and billions of connections ensure that they link to each other. Moreover, our nervous system has plasticity; in certain cases, other areas can perform the functions of traditionally known regions.

Areas of the brain involved in morality and lying

See below a simplified representation of the areas involved in our moral decisions. So it is obvious that discovering if someone is lying would not be so easy….. Remembering that, from a psychological point of view, lying is not only a matter related to memory but mainly related to our moral decision-making system. This is one reason why we have the eye movement misconceptions

Here is my advice: do not believe something is scientific if they do not show you their sources very well.

If you have made it this far, I recommend you read my article titled Characteristics of a Psychopath and you will see how many of the myth propagators have similar characteristics.

Regards

Sergio Senna

References

Bensley, D. A., & Lilienfeld, S. O. (2017). Psychological misconceptions: Recent scientific advances and unresolved issues. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 26, 377-382. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721417699026

Bensley, D. A., Lilienfeld, S., & Powell, L. A. (2014). A new measure of psychological misconceptions: Relations with academic background, critical thinking, and acceptance of paranormal and pseudoscientific claims. Learning and Individual Differences, 36, 9-18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2014.07.009

Boudry, M., Blancke, S., & Pigliucci, M. (2015). What makes weird beliefs thrive? The epidemiology of pseudoscience. Philosophical Psychology, 28, 1177-1198. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515089.2014.971946

Bronstein, M. V., Pennycook, G., Bear, A., Rand, G., & Cannon, T. D., (2018). Belief in fake news is associated with delusionality, dogmatism, religious fundamentalism, and reduced analytic thinking. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jarmac.2018.09.005

Colwell, L. H., Miller, H. A., Miller, R. S., & Lyons, P. M. (2006). US police officers’ knowledge regarding behaviors indicative of deception: Implications for eradicating erroneous beliefs through training. Psychology, Crime & Law, 12, 489-503. https://doi.org/10.1080/10683160500254839

Denault, V. (2015). Communication non verbale et crédibilité des témoins [Nonverbal communication and the credibility of witnesses]. Cowansville, Montreal: Yvon Blais.

Denault, V., & Jupe, L. M. (2017). Justice at risk! An evaluation of a pseudoscientific analysis of a witness’ nonverbal behavior in the courtroom. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 29, 221-242. https://doi.org/10.1080/14789949.2017.1358758

Denault, V. et al. (2020). The analysis of nonverbal communication: The dangers of pseudoscience in security and justice contexts. Anuario de Psicología Jurídica, 30(1), 1–12.

Gauchat, G. (2012). Politicization of science in the public sphere: A study of public trust in the United States, 1974 to 2010. American Sociological Review, 77, 167-187. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122412438225

Jupe, L. M., & Denault, V. (2018). Science or pseudoscience? A distinction that matters for police officers, lawyers and judges. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Kozinski, A. (2015). Criminal law 2.0. Georgetown Law Review, 44, iii-xliv

Lilienfeld, S. O., & Landfield, K. (2008). Science and pseudoscience in law enforcement: A user-friendly primer. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 35, 1215-1230. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854808321526

Majima, Y. (2015). Belief in pseudoscience, cognitive style and science literacy. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 29, 552-559. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.3136

Mehrabian, A., & Ferris, S. R. (1967). Inference of attitudes from nonverbal communication in two channels. Journal of consulting psychology, 31(3), 248.

Mehrabian, A., & Wiener, M. (1967). Decoding of inconsistent communications. Journal of personality and social psychology, 6(1), 109.

Nisbet, E. C., Cooper, K. E., & Garrett, R. K. (2015). The partisan brain: How dissonant science messages lead conservatives and liberals to (dis)trust science. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 658(1), 36-66. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716214555474

Pennycook, G., Cheyne, J. A., Barr, N., Koehler, D. J., & Fugelsang, J. A. (2015). On the reception and detection of pseudo-profound bullshit. Judgment and Decision Making, 10, 549-563.

Pennycook, G., & Rand, D. G. (2018). Lazy, not biased: Susceptibility to partisan fake news is better explained by lack of reasoning than by motivated reasoning. Cognition. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2018.06.011

Shen, F. X., & Gromet, D. M. (2015). Red states, blue states, and brain states: Issue framing, partisanship, and the future of neurolaw in the United States. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 658(1), 86-101.

Williamson, P. (2016). Take the time and effort to correct misinformation. Nature, 540(7632), 171. https://doi.org/10.1038/540171a

Other studies on lying and eye movement

Neurolinguistic Programming – Eye Movement

- Ertheim, E.H.W., Habbib, C. & Gumming, G. (1986) Test of the neurolinguistic programming hypothesis that eye movements relate to processing imagery. Perceptual and Motor Skills: Volume 62, Issue, pp. 523-529.

- Lapakko, David (1996). Three cheers for language: A closer examination of a widely cited study of nonverbal communication. Communication Education 46(1):63-67

- Test of the eye-movement hypothesis of neurolinguistic programming

- Thomason, T.C, Arbucklet., & Cady D. (1980) Test of the eye-movement hypothesis of neurolinguistic programming. Perceptual and Motor Skills: Volume 51, Issue, pp. 230-230.

- Wiseman R, Watt C, ten Brinke L, Porter S, Couper S-L, et al. (2012) The Eyes Don’t Have It: Lie Detection and Neuro-Linguistic Programming. PLoS ONE 7(7): e40259. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0040259

This post is also available in pt_BR.